A Pattern for Live Form Validation

· 12 min readThis post demonstrates a straightforward method for writing “live” client-side form validation. It is intended for intermediates or advanced beginners who understand the fundamentals of HTML and modern JavaScript (ES2015). Code samples in this post use ES2015 features and APIs that should be supported in the latest versions of major browsers, but will not work in older browsers.

Looking at the Requirements

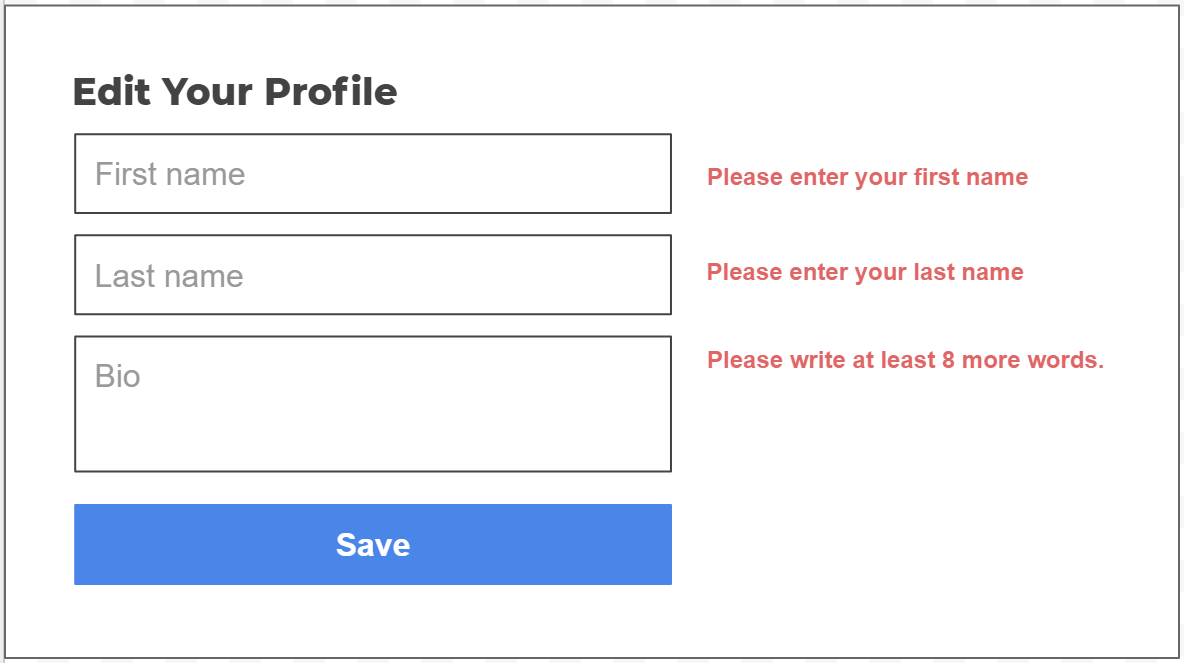

Suppose you are asked to build a basic user profile form to collect a person’s first name, last name, and personal bio. The info will need to be POST-ed to an API when the form is submitted, but not before doing some client-side validation.

Let’s say this is the mock-up you received from the designer:

At first glance, it looks like a simple form you’ve built many times before. You figure you’ll just validate the form when ‘Save’ is clicked and show any errors just like the mock-up. Then you read the written requirements from designer:

Profile Form Validation

For the best possible user experience, the profile form should show which fields are valid or invalid as the user works through the form. That is, form validation should be “live.”

This means:

- A field should not show any errors until the user has touched it.

- Once the user touches a field, show an error while the field is not valid.

- Error messages should disappear as soon as the error has been corrected.

- Clicking the ‘Save’ button should reveal all errors (or submit the form if there are no errors).

Field validation rules:

- First name - Cannot be blank.

- Last name - Cannot be blank.

- Bio - Cannot be blank, and must contain at least eight words.

Oh. “Live” form validation. Perhaps this simple form is not so simple.

To begin with, perhaps you are also a bit confused by the word “touched.” You aren’t sure what the designer meant by that.

So you go to the designer and talk through the UX with her. You come to understand that a field is “touched” once the user focuses on the field and then moves away from it. You take a look at a list of DOM events and decide that either onblur or onfocusout would work for detecting those exit events. So now you have a definition of “touched” that you can work with in code!

Let’s Write Some Code

Now that we understand the objective, let’s think through how to code this. We are certainly going to need some HTML markup for the form. Using the bare minimum markup, here’s what we get:

<form method="post">

<input type="text" name="firstName" placeholder="First name" />

<input type="text" name="lastName" placeholder="Last name" />

<input type="text" name="bio" placeholder="Bio" />

<button type="submit">Save</button>

</form>

Hopefully you already know that this form will work as written. When the user clicks the ‘Save’ button or presses the ‘Enter’ key inside the form, your browser will make a synchronous POST request to the current page URL. By default, the form data will be encoded in the request with the application/x-www-form-urlencoded content type. The server is then responsible for handling the request and returning a new or updated version of the page.

But… it’s 2018, not 1999. Users expect their interfaces to be smarter and more reactive. Let’s also suppose that this form is part of a single page app, so instead of a synchronous request that refreshes the page, you need to use JavaScript to make an asynchronous POST request that sends this data to an API endpoint encoded as JSON (application/json content type).

Let’s say the relative path to the endpoint is /api/profile. We could add a script to submit the form data asynchronously:

<form onsubmit="handleSubmit(event)">

<input type="text" name="firstName" placeholder="First name" />

<input type="text" name="lastName" placeholder="Last name" />

<input type="text" name="bio" placeholder="Bio" />

<button type="submit">Save</button>

</form>

<script>

function handleSubmit(event) {

event.preventDefault();

// Get the form, and create an object with the form data

const form = event.target;

const data = {

firstName: form.querySelector('[name="firstName"]').value,

lastName: form.querySelector('[name="lastName"]').value,

bio: form.querySelector('[name="bio"]').value,

};

// Asynchronously post the data

fetch("/api/profile", {

method: "post",

body: JSON.stringify(data),

})

.then(function (response) {

return response.json();

})

.then(function (data) {

// Success!

});

}

</script>

This is pretty straightforward. We added onsubmit="handleSubmit(event) to the form and wrote the handleSubmit function to read and POST the form data. We could go into greater depth about how to handle the server response and errors, but that’s not the focus of this post. We’re talking about live form validation, so let’s go back to that.

Data Modeling

In the above examples, we didn’t define a data model in JavaScript. Instead, the data was effectively stored in the input elements, and we could get to it by query-selecting all of the input elements and reading their .value attributes. In a way, this makes the form like a Plain Old JavaScript Object with the following structure:

const profile = {

firstName: "",

lastName: "",

bio: "",

};

So this is our “data model” for the profile, written in JS. And it’s likely that our API will expect to receive the data in this format, which is what we did in the asynchronous form example above. To make this object, all we had to do was read and copy the values from the form inputs.

But looking back at our requirements, we need to track more than the input values. We also have to track which inputs are ‘touched’. But since there is no such thing as input.touched, we can’t get this from the DOM in the same way. Instead, we will have to model input.touched in JavaScript and keep track using DOM events.

We can model which fields were ‘touched’ by extending our profile object from above. We can make firstName, lastName, and bio into sub-objects that not only store a value, but can also record whether or not the corresponding input has been touched:

const profile = {

firstName: {

value: "",

touched: false,

},

lastName: {

value: "",

touched: false,

},

bio: {

value: "",

touched: false,

},

};

We also need a place to put any errors we find in the profile data, so let’s also add an ‘errors’ Array. Further, let’s wrap both the profile object and errors list in a parent object called ‘state’ to keep everything grouped together.

const state = {

profile: {

// ...

},

errors: [],

};

If you are familiar with React or Redux, the idea of putting everything into one big state object might feel familiar. For those familiar with AngularJS: ‘state’ is similar to ‘scope’.

Syncing Data (Data Binding)

This looks good, and our data model now includes all of the values we need to track, but when the user interacts with the form, we need a way to keep ‘value’ and ‘touched’ up to date in real time.

Synchronizing the form with our data model is pretty straightforward: every time the form receives an oninput event, we can read the form data and copy it to our model. Meanwhile, we can listen for the onfocusout* event to know when a field was touched, since onfocusout is triggered when the user leaves an input field.

While we could attach event listeners for these events to each input, there’s no need to do so. Thanks to event bubbling, we only need to put them on the form, like so:

<form

onsubmit="handleSubmit(event)"

oninput="handleInput(event)"

onfocusout="handleFocusOut(event)"

>

<!-- ... form inputs -->

</form>

*If you are wondering why we use onfocusout here instead of onblur, it is because onblur does not support event bubbling. Therefor onblur will only work if you attach the event listener to each input field. In this case, it is simpler to use event bubbling.

Let’s update the event handlers:

const state = {

// ...

};

function handleSubmit(event) {

const formElem = event.currentTarget;

// Prevent form from submitting

event.preventDefault();

// Mark all fields touched

state.profile.firstName.touched = true;

state.profile.lastName.touched = true;

state.profile.bio.touched = true;

doUpdate(formElem);

// No errors. Save the data.

if (state.errors.length === 0) {

// In a real application, this is where we

// would make an Ajax call or call or

// form.submit() to save the form data.

alert("No errors - we can save the data!");

}

}

function handleInput(event) {

// Get the form element and update the profile

const formElem = event.currentTarget;

doUpdate(formElem);

}

function handleFocusOut(event) {

// Triggered when the user leaves an input (the input loses focus)

// Mark the input 'touched' and update the profile

const formElem = event.currentTarget;

const inputElem = event.target;

const field = profile[inputElem.name];

if (field) {

field.touched = true;

}

doUpdate(formElem);

}

function doUpdate(formElem) {

// Read the form data and update the state field values

const { firstName, lastName, bio } = state.profile;

firstName.value = getInputVal(formElem, "firstName");

lastName.value = getInputVal(formElem, "lastName");

bio.value = getInputVal(formElem, "bio");

}

function getInputVal(formElem, inputName) {

return formElem.querySelector(`[name="${inputName}"]`).value;

}

When using event bubbling, pay attention to the difference between event.target and event.currentTarget.

Take a moment to trace through the code… handleInput will update the profile object every time the form receives input. Meanwhile, handleFocusOut is triggered whenever the user leaves an input field. It records that the input was touched and also updates the profile data. We’ve also changed the handleSubmit function to mark all fields as ‘touched’ and then update the profile data. If there are no errors at this point, it will submit the form …of course we still haven’t added any validation at this point.

Finally, doUpdate (with the help of getInputVal) is where the form data is actually copied to the profile object. doUpdate is a separate function so that we don’t have to duplicate this code inside each event handler. Every event listener calls doUpdate at some point.

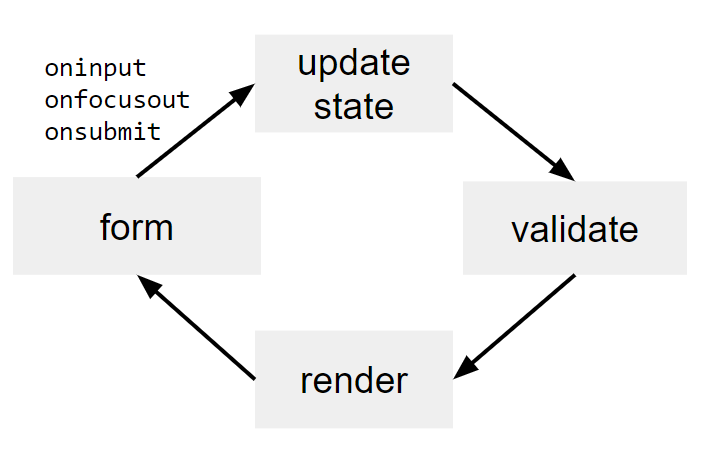

Data Flow

So far we have defined a data model to hold the state of our form fields and have written event listeners to keep our data model “live” and in sync with changes to the form inputs in the interface.

When the user takes action, DOM events trigger our event listeners and begin a feedback loop which reads the form data, validates it, and updates the form accordingly, as illustrated here:

Two important things about this design are that (a) data updates flow in one direction only and (b) the DOM is always updated all at once at the end of the chain of events—NEVER in the middle of the loop.

If this pattern seems unfamiliar to you, I encourage you to go read about data binding and one-way data flow, both extremely important and powerful concepts in modern web interface programming. These are the backbone of reactive frameworks such as React, AngularJS, and VueJS.

Complete the Loop

So we have form events updating our data, but to complete the loop we still need to check for errors and update the form UI, so now let’s make this interface come alive!

In order for field errors to appear and disappear “live,” we will need to validate the profile data every time it changes. In our code above, the profile data is always updated inside of the doUpdate function. So we can modify this function to always validate the profile data and update the ‘errors’ list after reading the latest form values:

function doUpdate(formElem) {

// Read the form data and update the state

// ...

// Validate the new profile data and update state.errors

state.errors = validateProfile(state.profile);

// Render the field errors

renderErrors(formElem, state);

}

function validateProfile(profile) {

const errors = [];

// Validate the 'first name' field

if (!profile.firstName.value) {

errors.push({

field: "firstName",

message: "Please enter your first name.",

});

}

// Validate the 'last name' field

if (!profile.lastName.value) {

errors.push({

field: "lastName",

message: "Please enter your last name.",

});

}

// Validate the 'bio' field

const requiredWordCount = 8;

const bioWordCount = profile.bio.value

.split(" ")

.filter((i) => i !== "").length;

if (!profile.bio.value || bioWordCount < requiredWordCount) {

const wordCountDiff = requiredWordCount - bioWordCount;

errors.push({

field: "bio",

message:

`Please write at least ${wordCountDiff} more word` +

(wordCountDiff > 1 ? "s" : "") +

".",

});

}

return errors;

}

function renderErrors(formElem, state) {

// First remove any existing error messages

const oldFieldErrors = formElem.querySelectorAll(".field-error");

for (let err of oldFieldErrors) {

err.parentNode.removeChild(err);

}

// Then add any current error messages

state.errors.forEach((error) => {

const field = state.profile[error.field];

// Only display errors if the field has been touched.

if (field.touched) {

const fieldErrorSpan = document.createElement("span");

fieldErrorSpan.classList.add("field-error");

fieldErrorSpan.innerHTML = error.message;

formElem

.querySelector(`[name="${error.field}"]`)

.parentNode.appendChild(fieldErrorSpan);

}

});

}

This is another big chunk of code, but it’s rather simple. Everything revolves around the validateProfile function, which simply takes in a profile object, checks each field, and generates a list of errors. To validate more fields, you need only add more checks to this function. Validating first and last name are simple (we’re just checking that they are not blank), but you might say the validation on the bio field has some extra flair.

The errors generated by validateProfile are objects in this format:

{

field: fieldName,

message: errorMessage,

}

With this errors list, we can check if the entire form is valid (errors.length is 0), and we can also loop over the list of errors to handle each one, which is what renderErrors does.

One important thing to notice is that we’ve tied everything together by using consistent names throughout. For example, we have profile.firstName in our state. This same name appears in the error objects and on the corresponding input (ex: name="firstName"). This makes it easier to keep everything glued together. If instead the input had a different attribute such as name="first_name", then we would have to find a way to map firstName to first_name, and our code would become rather more complex.

The Final Result

And with that, our code is complete! Try playing with the form below. It has not been styled, but it should now fulfill all of our designer’s requirements. Field errors should appear only after you have ‘touched’ a field, and you should be unable to submit the form, until all fields are valid.

View the complete code for this example.

Final Thoughts

Live form validation is a very common requirement of modern web applications, but even in 2018, doing it well is not as simple as it seems. As we’ve seen, the problem also provides a good lead-in for discussing important UI programming concepts like data binding, one-way data flow, pure functional programming, and reactive programming.

The pattern described in this post has served me well a number of times. At its core, you simply pass your data model into a validation function that generates a list of errors. It’s neither fancy nor clever, but it’s very effective. Perhaps most importantly, it makes adding and removing form fields easy to do and reason about.

I also felt it was important to do this without using any frameworks, both to make the code easier to follow, and because the raw power of “VanillaJS” always deserves more attention.

Still, the final code is not as “simple” as I would like. The messiest bits have to do with DOM manipulation. Without data binding or a templating language, that mess is liable to grow and create bugs as you add more form fields and validation rules.

Lastly, once you understand the fundamental pattern at work here, adapting it to a reactive framework like VueJS is a breeze. This will definitely be the subject of a future post.

Additional Challenges

A. (easy) Can you modify the code to disable the ‘Save’ button whenever the form has invalid fields?

B. (easy) Can you style the form to match the mock-up?

C. (medium) Can you add an email field to the form with validation?

D. (harder) The designer is thrilled that you were able to do the live field validation, and now that they can see it in action, they have a new idea. She asks, “Can we also show which fields are valid? I mean, if a field is ‘touched’ and ‘valid’ can we put a check box next to it, just like the error message to show the users it’s good to go?” Well, can you?