How I Ham (🍖📻 Ham Radio) - Part 1

· 12 min readI’ve been a licensed ham radio operator for five years now, so I thought I’d reflect on my progress and how I am doing ham radio today in 2024.

Microelectronics Were the Gateway

My path to ham radio began in 2017. I was working on some Arduino projects. That turned out to be my “gateway drug”. At the time, I wanted build and deploy some low power wireless sensors in my apartment. We had a loft area that would heat up in the summer, and I was curious to monitor the temperature difference in various rooms. I also built a moisture sensor to help us remember to water our house plant.

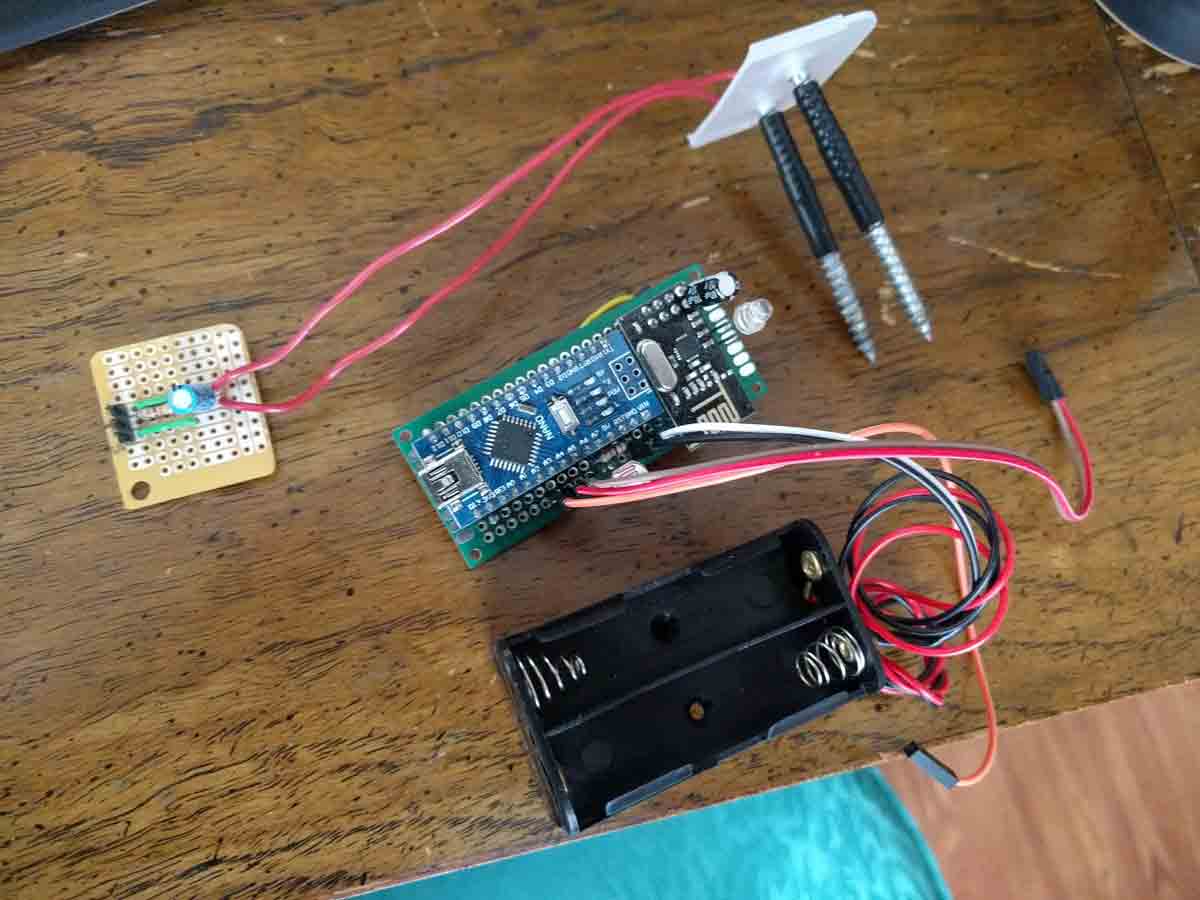

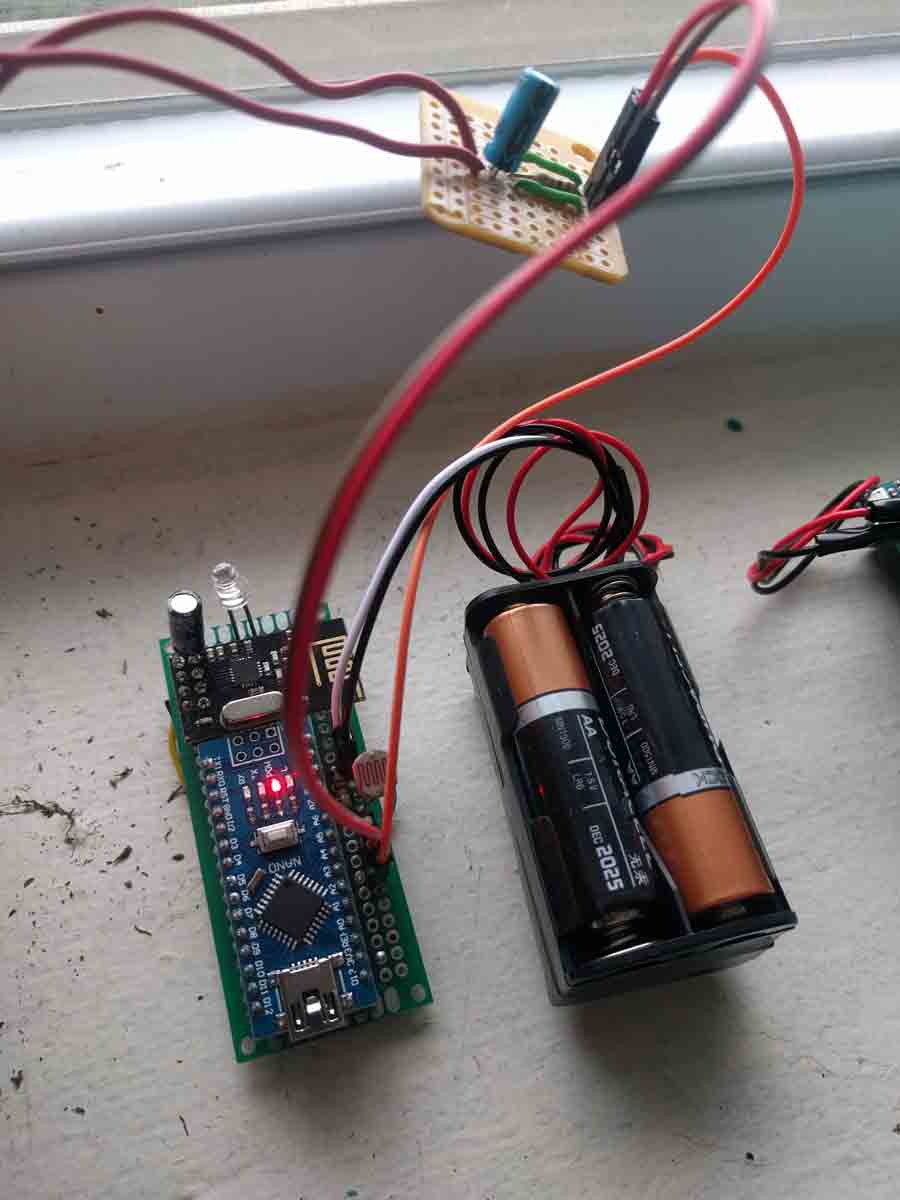

Here are some shots of the sensors I built. They are each based on an Arduino Nano with a NRF24L01 radio module. The first sensor is a homebrew moisture sensor that uses two screws as the anode and cathode to stick in the dirt. It works by measuring the resistance between the screws. More resistance means less moisture.

The moisture sensor board also has a photoresistor to measure light levels. Both the moisture and light values were reported as part of the wireless payload.

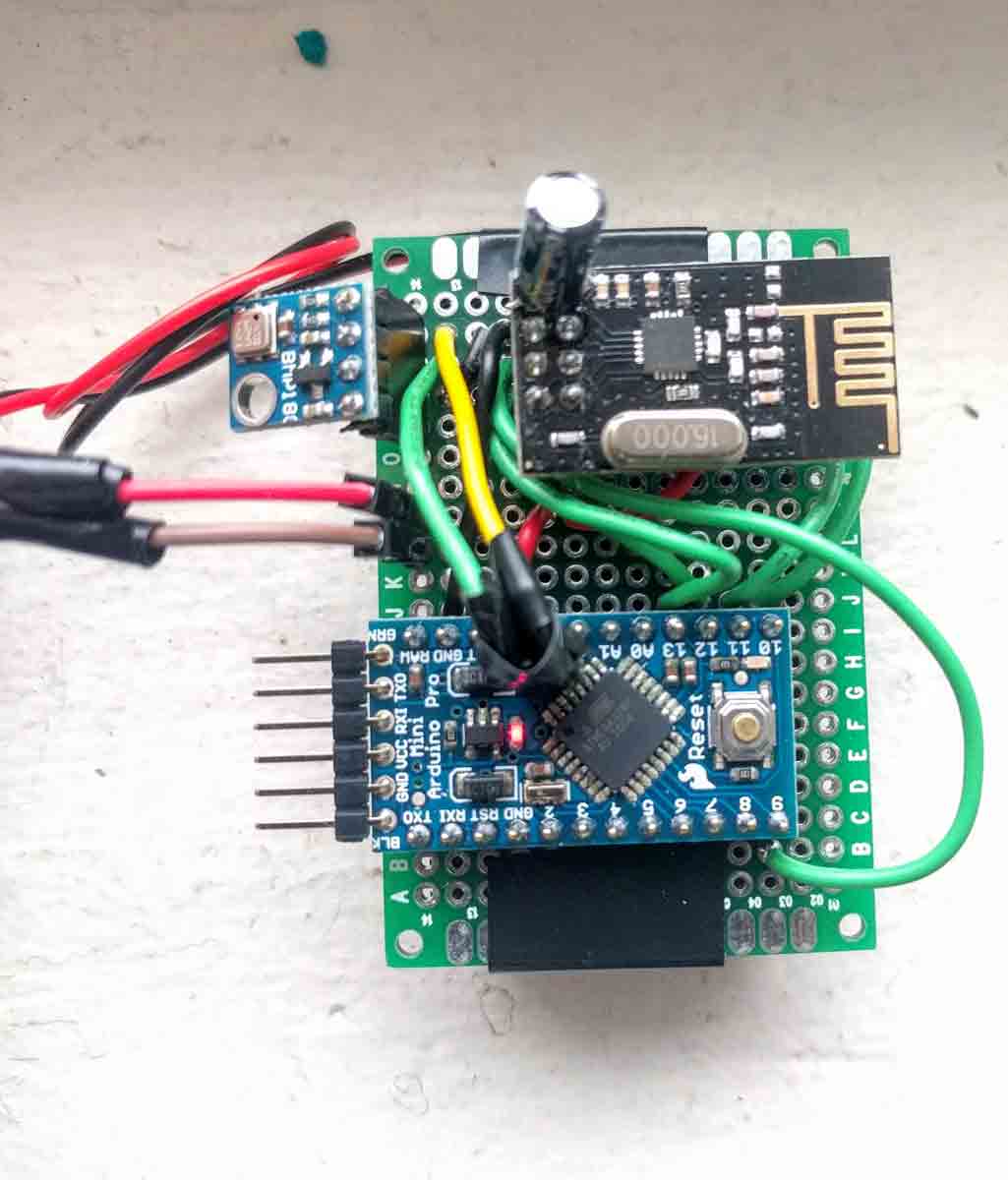

And here’s a separate board with a temperature and barometric pressure sensor:

Both boards were powered by two AA batteries and could survive for many months, even a year, with proper low power optimizations. The main goal was low power and my other goal was low cost. For instance, some out-of-the-box moisture sensors can cost $20-50. My recycled screws-and-plastic sensor cost at most $2. All together, each of these boards easily cost less than ten dollars in parts.

Not pictured is the old Raspberry Pi I used as a receiver and server. Every few minutes the sensors would wake up, take a measurement, and chirp it out of their transmitters. The Raspberry Pi was always listening for these incoming signals. It translated them into text and wrote them down to append-only time series files. I then built a small Flask app with API endpoints that would read these files, filter them, and display the data in a web page.

That project is long dead, but the code is still on GitHub. One self-imposed requirement of this project was that I would not use WiFi or Bluetooth. I wanted to have a lower-level understanding of what the radio transmitters were doing. For the project I selected NLRF24 radio modules, and I even designed a little byte-by-byte protocol for them to exchange information.

Down the Rabbit Hole

I can’t remember precisely when or how I fell down the radio rabbit hole, but I know for certain that it started when I was reading about how the NLRF24 modules worked. I started encountering many unfamiliar terms and concepts about radio frequencies, modulation, propagation, etc.

I dug deeper and that must be when I came across ham radio. It may seem silly, but I was really into the idea that I could have my own unique, internationally-recognized callsign. I was also fascinated by the more “magical” aspects of radio: the fact that radio is all the invisible wavelengths of light and is therefore literally an unseen force all around us at all times that transmits information at lightspeed. I often say this is the closest thing to fairy tale magic that you can find in the real world!

In the background of this, I love languages and code. I had always wanted to learn Morse Code. And like many others I also appreciated the emergency preparedness and self-reliance aspects of “owning your comms” end to end.

I was gearing up to get my license then. Naturally, I followed the standard beginner’s advice and bought a Baofeng UV-5R from Amazon. I recall that I did some listening. I managed to find a few repeaters and learned some radio basics, but I was honestly a bit mystified. It is admittedly difficult to step into ham radio at first, especially if you expect - as I did - to be able to Google all the answers. Perhaps due to its age and long legacy, ham radio is much less of an “online” hobby than others. Books, magazines, and engaging with other hands-on participants are still the best way to learn.

Later that year, we moved to a new house. At work, we were also launching the new business that would eventually become ThinkNimble. My personal electronics and radio projects ended up being boxed away for a couple years.

Getting Licensed

In 2019 ThinkNimble had begun to stablize, and our team was growing. It was still a rather stressful time, and so I found myself looking for hobbies that would help take my mind of work, while still being rooted in creativity and technical problem solving. This brought me back to ham radio.

I became an avid follower of Josh Nass’s (KI6NAZ) Youtube channel, the Ham Radio Crash Course (HRCC). I’ve learned a TON from Josh. I’m not sure that I could have gotten oriented without his work. I’ve been a “Producer” level Patreon patron of his for several years now. My wife and I enjoy listening to the podcast that he does together with his wife.

From HRCC, I got wise to hamstudy.org, which is IMO the best way to quickly study and obtain your license. For instance, I challenged my wife to study for 30 minutes a day until her proficiency was above 80%. She’s a good sport, but definitely not as interested in “technical stuff” as I am. Well, using HamStudy, she passed her Technician exam on the first try after only two weeks of studying like this!

If you want to do more than just pass the test, then the ARRL handbooks are a must. Reading through these handbooks were the best way I found to actually learn and fully understand the ham radio concepts on the test. Again, this is all a bit more difficult to find online than you might be used to, though it’s gradually changing as a new generation of hams come online.

I finally got licensed as a Technician in May 2019, callsign KC3NKM. A local ham club in Maryland was offering tests, so I drove out there. Online testing was not yet a thing! The guys were nice, and they seemed impressed at how quickly and precisely I completed the test. I’ve always been good at memorizing things, and in hindsight I studied way more than was necessary. They enthusiastically congratulated me, and it was a lovely welcome to the community.

I started getting into VHF/UHF, first with a Yaesu FT-2DR handheld and then with an FTM-400 “mobile” radio that I kept on my desk at home. I bought a vertical antenna and installed it on my chimney. To do so, I had to get up on our hot tin roof on a balmy 90-degree DC day. In order to route the coax into the house, I bought a huge drill bit and a hammer drill, which I used to put a 2-inch hole through my foundation into the basement where I have my office and now my “ham shack”. For a few years, this hole was plugged with nothing more than hot glue - more on that later.

From there, I got familiar with the local repeaters, programmed my radios, and started listening in regularly. A couple times I checked into a local weekly “net” that is based in Rockville MD. I learned about Yaesu System Fusion and other digital modes. Through all this, I did a lot more listening than speaking. I was, and still am, very shy.

Lock Down

We all know what happened in 2020. At this point, I felt like I was reaching the end of my interest in VHF/UHF, and I was frustrated with the limitations of the Technician license. I had learned enough to realize that HF is where the real fun is, offering both long distance contacts and above all digital modes like FT8.

FT8 really appealed to me because I could make long-distance contacts without having to speak on the radio. To this day, I’ve made most of my almost 2000 confirmed contacts this way, reaching from South Africa to New Zealand, Mongolia, Japan, and all over Europe.

So when the lockdowns began, my interest in emergency preparedness was immediately rekindled and I made a sprint to get my General license. In early 2020, my target was to get an emergency HF radio kit together in time for Field Day, which happens at the end of June.

Although I did not have extensive HF privileges yet, I went ahead and bought an IC-7300. It is a great radio, and still the best entry-level HF radio by many accounts. I also bought some speaker wire and began assembling basic wire antennas. Pictured here are wires for 10, 20, and 40 meters along with radials. They actually worked pretty well!

Like so many other things, ham radio licensing tests quickly went online. I again used HamStudy to prep for my General license, and I again easily passed the exam, this time over Zoom from my kitchen table. I now had my General license!

My next step was to choose and obtain a vanity callsign. I didn’t love the default callsign I was assigned. I ended up choosing W3WYM. The W3 prefix is appropriate for Zone 3 - this part of the East coast. And then “WYM” is sort of like an abbreviated way to say “William”. Spelled phonetically, you might also say “Whiskey Yankee Microphone”. Well, I’m a Yankee, and if you catch me talking in a microphone, then whiskey is likely involved 😅.

This concludes part 1 - I will publish and link part 2 soon!